Both the coronavirus pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement create opportunities to reshape cities in more equitable ways.

(The following is the first of a three-part essay that breaks down overlapping crises that are reshaping America’s cities. The initial installment examines why predictions of the impending end of cities are overblown — and why they may come back stronger.)

As the coronavirus crisis and its economic, social and political fallout swept across America, it seemed the death of cities was imminent. Story after story charted a “great urban exodus,” as the affluent and advantaged from New York City fled to the suburbs, summer cottages in the Hamptons and Hudson Valley, or their winter getaways in Palm Beach and Miami. This gloomy thesis was reinforced by a rapid succession of calamities that struck at cities in the wake of the pandemic — the most severe economic collapse and job loss since the Great Depression; the metastasizing crisis for small businesses, retail, and arts and culture; and looming fiscal deficits for cities.

All of this was followed by the wave of protests set in motion by the brutal police murders of George Floyd at the hands of the Minneapolis police, the slaying of Breonna Taylor who was shot eight times by Louisville police as she slept in her bed, and the killing of Rayshard Brooks at a Wendy’s drive-thru in Atlanta, not to mention the savage murder of Ahmaud Arbery by a pair of would-be vigilantes in Glynn County, Georgia. These acts reinforced and reflected the long history of racial division and injustice that stand at the root of American society. And at the same time, the Covid-19 virus took its greatest toll on long-disadvantaged black and minority communities — and its economic fallout hit hardest at them. In city after city across the U.S. and around the world, people of all races and classes emerged from months of lockdown and social distancing to join in the fight against systemic racism, a virus that has ravaged America for far longer than Covid-19.

Would these intertwined crises put an end to the great urban revival of the past quarter century? It would be one thing if the death of cities thesis was limited to the familiar chorus of anti-urbanists and city bashers, but it was picked up and reinforced by the major media and even by some leading economists. “I fear that the prominence of the city, and particularly city centers, will decline,” is how Stanford University’s Nicholas Bloom put it. “First, the pandemic has made us much more aware of the need to reduce density. That means avoiding the subway, elevators, shared offices, and communal living. Second, working from home is here to stay. So why not live further out, where housing is cheaper?” As another commentator starkly put it, the big question was whether or not those who left cities would “ever return.”

Are People Really Leaving Cities?

Interest in real-estate listings outside of major U.S. cities increased among some urban dwellers in April compared with a year earlier; in others, it dropped.

Source: Zillow data

Let’s not get too carried away. While the justifiable fear of a once-in-a-century pandemic may lend such dystopian predictions greater resonance, they are but the latest in a long-line of such prognostications. When the pandemic and all its related crises finally ebb and we are on the road to recovery a couple of years from now, we will look back and see that the roster of the world’s leading cities is unchanged. New York and London will still be its leading financial centers; the San Francisco Bay Area its hub of high technology; and Los Angeles its center for entertainment and film. Shanghai, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Singapore, Paris, Toronto, and Sydney will all continue to be great global cities.

As overwhelming as the current overlapping crises may seem now, cities have suffered and survived far worse. Over the long course of history, cities have weathered all manner of pandemics and economic crashes, not to mention natural and unnatural disasters like wars, hurricanes, and earthquakes, none of which has permanently staunched their growth. Urbanization has always proven the greater force — stronger than the devastating Black Plagues that began in the fourteenth century, the deadly cholera outbreaks in nineteenth century London, and the horrific tragedy of the Spanish Flu, which killed as many as 50 million people worldwide between 1918 and 1920. Each and every time, the economic power of cities — their ability to compound innovation and productivity by compounding the talent of ambitious and creative people — has been more than enough to offset the destructive power of infectious disease.

When all is said and done, the Covid crisis and the wave of protest and unrest that has followed it may open up a moment when we can put our cities on a better trajectory, forcing them and all of us to at long last address the deep fundamental challenges of race and class division that stand at the heart of our society. Separately and together, today’s crises of urban America underscore the need to rebuild our cities, economy, and society in ways that are better, more just, more inclusive, and more resilient.

New York’s Resilience

No American city has been as hard-hit by the coronavirus as New York, where roughly 22,000 residents have died to date. The Covid crisis and the fallout from it are just the most recent in a series of black swan-like events — the terrorist attacks of 9-11, the economic and financial crash of 2008, and the devastating floods of Superstorm Sandy — that have rocked that city over the past two decades. The city’s obituary was written and rewritten each time, and each time it came back stronger.

A close look at the actual data suggest that much of this exodus is temporary and less extensive that doomsday predictions have made it out to be. A New York Times analysis of cell phone data found that 420,000 people decamped from the city. But that figure includes huge numbers of college students who hail from other locations anyway. A separate Times analysis of mail forwarding found that 137,000 people or 1.6% of the city’s population had their mail forwarded to addresses outside the city in March and April, most of them to outlying areas of the region, with just a fraction of a percent to other cities or metro areas. As the next installment of this essay will show, most who are likely to stay away from the city are families with children who would have left the city anyway in the coming year or two.

Even the deadlier pandemic of the Spanish Flu, which killed a significantly greater share of New York’s population at the time, did not dim the city’s ascent as the world’s leading economic and cultural center. In the decades that bracketed that pandemic, spanning 1910 and 1930, greater New York’s population surged from 4.8 to 6.9 million. Far deadlier pandemics did little to damp down the long arc of urbanization. Although the Black Plague killed as much as half the population of Italy’s great urban centers like Siena, Orvieto, Florence, and Milan, people flocked to them from the countryside in the decades and centuries after because they offered not just higher wages, but tax exemptions, and in some cases, even citizenship, to attract foreign merchants, artisans, and laborers. Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year describes how the combined blows of a pandemic that killed a quarter of London’s residents in a matter of months, followed a year later by a fire that burned most of the city to the ground, laid the foundation for a spectacular economic rebound, as people rushed into the city to rebuild it. That city’s role as the world’s leading financial center of the time actually expanded in the wake of its deadly cholera epidemics in the nineteenth century.

Major Pandemics

Deadliest outbreaks since the beginning of the 19th century

Source: Visual Capitalist

Despite what urban doomsayers would like to have you believe, leading industries like finance, media, entertainment and high-tech are unlikely to move significantly away from New York or other superstar cities. Just two broad mega-regions, the San Francisco Bay Area and the Acela Corridor — spanning Boston, New York and Washington, D.C. — are home to roughly three-quarters of venture capital investment in startup companies. In the decade-plus period running from 2005 to 2017, innovation-related industries and jobs have become more concentrated in just five leading metro areas on the East and West Coasts, which accounted for more than 90% of the growth of innovation-related jobs over this period.

Ultimately, today’s crises will likely do little to alter the decades-long locational preference or “spikiness” of these key industries for leading superstar cities. These jobs and industries will remain concentrated in those places, not simply because their founders or CEOs like fancy office towers or because their workers prefer to live in urban centers; they are there because of the enormous productivity advantages those locations carry with them. The tight clustering of workers, firms, customers, suppliers, universities, banks, and other lenders and investors in these places — what economists refer to as “agglomeration economies” — is the source of substantial knowledge spillovers and other externalities which drive higher rates of innovation and output per worker. In the early days of the Covid-19 crisis, the Nobel prize winning economist Paul Romer firmly dismissed the notion that the virus would hinder the growth trajectory of cities. “The underlying economic reality is that there is tremendous economic value in interacting with people and sharing ideas. There’s still a lot to be gained from interaction in close physical proximity,” is the way he put it. “For the rest of my life, cities are going to continue to be where the action is.”

The Density Debate

Commentators were quick to lay the blame for the intensity of the Covid-19 crisis in New York on the city’s density. But this is far too simplistic; the high density of even teeming, highly vertical cities does not have to be a fatal flaw. Some hyper-dense Asian cities, like Singapore, Seoul, Hong Kong and Tokyo, succeeded in managing the initial outbreak quite well, though they may be vulnerable to later flare-ups. And San Francisco, the second-densest city in the U.S., had much more success than New York at limiting the impact of the virus.

Covid-19 has not only taken root in dense, global cities, but in several other kinds of places. It spread through workers and factories in interconnected supply chains in the industrial centers of Wuhan, Detroit, and Lombardy. Global resorts on the Alpine ski slopes of Italy, Switzerland and France, and their counterparts in the Rocky Mountains, were also well-known hotspots for the virus’s spread. By late April and early May, the virus was spreading faster in rural or non-metropolitan areas than urban centers.

It is not density per se, but overcrowding that does the most to drive the spread of the virus. This is true not only of the poor, overcrowded communities of New York, the favelas of Brazil, and areas of concentrated poverty and deprivation in other large cities, but in small remote rural areas packed with multi-generational families. In some of those places, like the Navajo reservation in the Four Corners region of the American Southwest, the pandemic was even deadlier on a per capita basis than it was in New York City. As one commentator aptly put it, “When it comes to density, the trick is picking a scale. Covid-19 isn’t a problem of square kilometers, but one of square meters — of the number of people per unit of housing.”

Detailed statistical analyses by the urban economist Jed Kolko found that density is one of several factors associated with higher Covid-19 death rates across the US, along with overcrowded housing and having larger households, aging populations, higher levels of income inequality, larger concentrations of African Americans, and colder climates. The urbanist Max Nathan suggests that density has played less of a role in London and the U.K., decreasing as the epidemic spread from central London to outlying suburbs and smaller cities and metro areas. Like Kolko’s, his analysis also finds overcrowding, larger households, older populations, and socio-economic deprivation to be significant factors in the impact of Covid-19 in communities in the U.K.

As overwhelming as Covid-19 and its related crises may seem today, they may ultimately help to arrest a series of developments that have worked to undermine cities. The past decade or so has witnessed growing racial and economic inequality, escalating housing prices, and hyper-gentrification which have pushed minorities, working-class and middle-class people out of leading cities. Once lively, diverse, and creative urban neighborhoods have been transformed into veritable gated communities for the wealthy, many of them filled with absentee owners.

Taken together, these trends have shaped a deep and vexing new urban crisis — a crisis not just of cities but of late capitalism broadly. But, the combination of shrinking demand for offices and commercial real estate, fewer buyers for an already overbuilt luxury housing market, and the ongoing carnage of urban retail will make urban real estate significantly more affordable. Cheap space after all, as Jane Jacobs liked to remind us, remains the fundamental enabler of urban dynamism. Even as the economic fallout from the pandemic hits hard at the restaurants, cafes, boutiques, galleries and music venues that shape the intricate sidewalk ballet of urban life, it will also enable cities to reset and recharge their creative scenes. In short, it offers a chance to rebuild less divided and more equitable urban spaces.

‘I See Progress’

Combined with the recent wave of urban protest, we may have arrived at an historical moment where sweeping progressive change in our cities and society is possible. Where naysayers see what is happening today as a replay of the late 1960s, the rise of such a broad multi-racial, cross-class coalition is a key force, if not the key force, that can ultimately rebuild our cities on a more inclusive and more resilient footing. As my former Atlantic colleague Ta-Nehisi Coates recently told Ezra Klein: “I can’t believe I’m gonna say this, but I see hope. I see progress right now.”

I was just nine years old when I witnessed the occupation of my hometown of Newark, New Jersey. Driving through the city with my father, I saw burning buildings, tanks, and heavily armed police and National Guardsmen. These are the formative events of racial injustice that shaped my own life-long interest in cities and urbanism.

While there are some similarities between what happened then and what is happening now, there are also crucial differences. Then as now, police brutality was the match that ignited the powder keg. On the evening of July 12, 1967, a black taxi driver was savagely beaten by white policemen. A crowd formed outside the precinct where he had been taken and things devolved from there. Seven thousand state and local police and National Guardsmen were deployed, and as most eyewitness accounts attest, they ran riot themselves. When the smoke cleared, 26 were dead, the majority of them black citizens, and more than 700 injured; 1,000 people were arrested and jailed. By the end of that long hot summer, there had been riots in Atlanta, Boston, Cincinnati, Buffalo, Milwaukee, Rochester, and Minneapolis and many other cities, small and large — more than 150 in all.

Back then, American cities were in the midst of a long process of disinvestment and capital flight, as business, industry, and the middle class decamped to the suburbs in what the economists Edgar Hoover and Raymond Vernon called the great “flight from density.” My own parents had left Newark for the working-class suburb of North Arlington in 1960. As urban centers hollowed out, they became what neoconservatives would sneeringly call “reservations” or “sandboxes” for poor minorities.

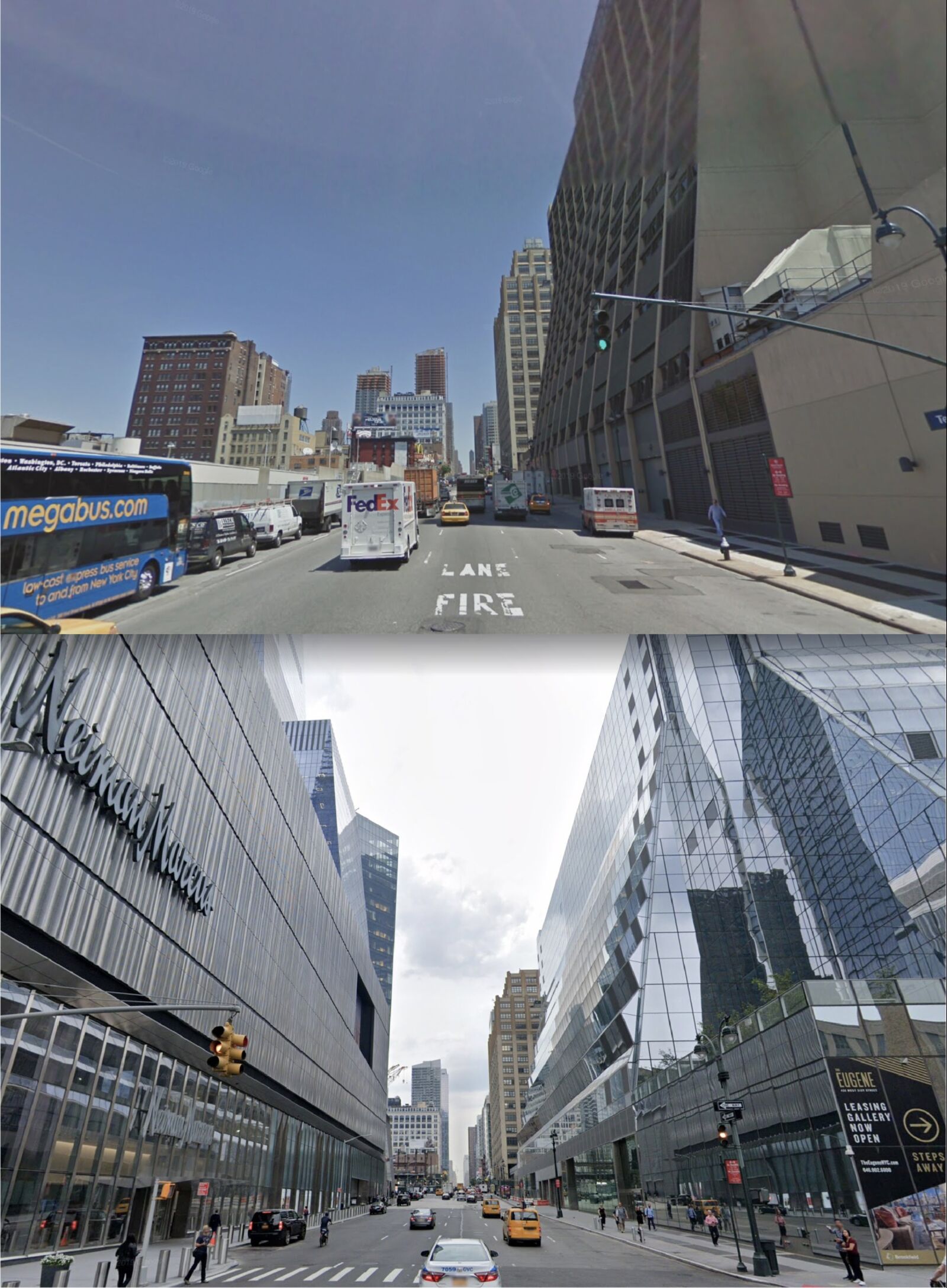

But in what has been called a “great inversion,” techies, knowledge workers and the affluent have flowed into cities, and leading industries have returned to urban business districts. In contradistinction to the old urban crisis of economic decay, we are experiencing a new urban crisis of “success” marked by rampant unaffordability, third-world levels of inequality, and racial and economic segregation. The physical manifestation of this are the darkened luxury towers that dot the high-end residential districts of New York and London, which function as an investment vehicle for the global super-rich but where few if any people actually live.

The very location of the unrest in today’s cities underlines the differences between what is happening today and the urban crisis of the 1960s. Back then, unrest was largely confined to the poor and minority neighborhoods. Today’s targets have been downtown commercial districts and luxury shopping areas like New York’s Soho, Atlanta’s Buckhead, and Southern California’s Beverly Hills.

The composition of the protests is also very different. Today’s demonstrations are multiracial and include families and professionals as well as young people and students. “One cannot but be struck by the significant proportion of protesters who are white, Hispanic, and Asian,” is the way the Harvard sociologist Orlando Patterson framed it. “I think it has to do with the moment we’re living right now. People seemed horrified that we’re seeing this sort of thing after all these years, but they also sense that something is profoundly wrong.” Or, as the academic and journalist Jelani Cobb tweeted on May 30: “You know we’re in uncharted territory when something happens in Minneapolis and they’re setting cars on fire in Salt Lake City.” While America remains divided, those divides no longer cut so neatly across affluent white suburbs and poor minority cities. Cities themselves are more racially and economically diverse.

If the urban unrest of the late 1960s seemed to signal the death and decay of cities, the urban unrest of today signals their resurgence and holds within it the seeds of their progressive remaking. Back then, it was not just cities that were on the downswing; the great urban policy experiments and commitments of JFK’s Great Frontier and LBJ’s Great Society were also on the decline. With his popular support eroding by the deepening quagmire of Vietnam, Johnson ceded the 1968 race to his vice president Hubert Humphrey. Richard Nixon won the election, running in part on a law and order platform that was aimed at the “silent majority” of white working-class voters. Today, it’s Trump’s anti-urban, anti-city policies that are on the downswing; his hollow threats to deploy federal troops to “dominate the streets,” rebuffed by mayors across the country, have only served to further weaken his already dysfunctional administration. Trump likes to brag that he won the popular vote in more than 2,600 American counties while Hillary Clinton didn’t even have 500 in her column. But those counties she won — all of them in large metropolitan areas — account for more than two-thirds of America’s economic output.

Not only are cities on the upswing, we are in the early stages of a new wave of urban policy innovation, which is occurring from the bottom up in cities, our true laboratories of democracy. Even before the current crises, cities were beginning to address the mounting challenges of racial and class division, inequality, police reform and worsening housing burdens. Coalitions and networks of mayors, urban leaders, neighborhood and civic groups, philanthropy, and public-private partnerships were already moving on all of these fronts to develop new and better strategies for inclusive urban development. The current crises have given these initiatives greater salience and urgency. And, the racial and economic diversity of cities and of today’s urban protest movement give them heightened political resonance.

We are seeing the coming together of a political force that can spark a new urban agenda and much more. Front-line service workers, our true heroes, are demanding — and deserve — higher wages and job protections. The growing ranks of unemployed and under-employed are demanding — and deserve — an expanded social safety net, universal health care coverage and better schools. Black Lives Matter is demanding — and requires — real police reform that redirects funding from policing per se to initiatives that reduce violence and promote social stability by strengthening the fabric of disadvantaged communities. That will also require much-needed investments that at long last address the root causes of concentrated poverty and of systemic racial and economic inequality. This coalescing movement represents a political force that is stronger and more potent than anything we have seen in decades.

It is no longer possible to ignore our cities, which remain our underlying engines of innovation, economic growth, and job creation, and the vanguards of a healthier, more sustainable and resilient future. Remaking and rebuilding urban America to be far more equitable, just and inclusive is the necessary first step in the long-overdue process of healing and recovery for our nation as a whole.

(click on the following link for the complete article)